Minnesänger

Minnesänger

Troubadour poetry leaves a clear footprint in the German-speaking territory of the Holy Roman Empire roughly between the 1170s and the 1230s. The close family, political, and economic ties that this territory maintained with the Romance language area, together with the fluid interactions between European courts, enabled it to acquire early knowledge of the songs that were being composed in the Occitan territory. This must also have made it easier for the subsequent production of music and songbooks, or lyrical manuscripts, to spread beyond linguistic borders. We can be even more certain that all the later Minnesänger knew in greater or lesser detail the songs from the French, Occitan, and Italian courts (and we can similarly assume that they in turn were also aware of the main German tendencies in this respect).

Nevertheless, although we can detect a clear relationship between German compositions and French and Occitan troubadour songs in the last three decades of the 12th century (with imitation of themes and poetic forms and probable contrafacta), we can also see evidence soon after that period of the consolidation of forms and themes clearly differentiated from these traditions, which govern the entire evolution of the genre until the 15th century.

The term Minnesang is made up of Minne (‘love’ in Middle High German) and sang (‘song’). Derived from this, the term for the author or performer of a love song is Minnesänger. In Romance-language scholarship, they are also referred to using the Anglicism Minnesinger. The term established a difference between love songs and other types of songs (political, satirical, religious, moral, or didactic). There is something in this division: the love song genre is, in general, largely discrete and shows little variation over the generations; the authors are by and large figures from the nobility or, in any case, poets who do not write any other type of songs; consequently, songbooks tend to separate the genres.

In contrast, all songs that are not love longs are grouped together under the complex term Sangspruchdichtung, which combines artistic poetry (Dichtung) with song (Sang), and the biblical and Classical tradition of sayings or proverbs (Spruch). These political and satirical songs, similar to the troubadour sirventes or cobla, as well as religious poetry (which does not appear in German lands until around 1200 with Walther von der Vogelweide), were written by troubadours who were not from the nobility, in other words professional and itinerant poets (called meister, ‘masters’). Unlike the love songs, this genre undergoes an intense development throughout the 13th century.

In fact, the fundamental transformations in form and music of the 13th and 14th centuries in the German-speaking lands all come from the Sangspruchdichtung. Some important masters of the late 13th and early 14th centuries (Frauenlob, Regenbogen, Marner, and Heinrich von Mügeln) created a school of poetry, in some cases perhaps even literally. This fact, on the one hand, determines the genre throughout the 14th and 15th centuries and, on the other hand, leads to the establishment of schools of song in the 15th century, in predominantly bourgeois urban environments. In terms of their music and form, these schools hark back to the old masters and are consequently known as ‘master singer schools’ (Meistersängerschulen), a cultural phenomenon characteristic of German cities in the 15th and 16th centuries, but which endures in isolated parts until the 18th century.

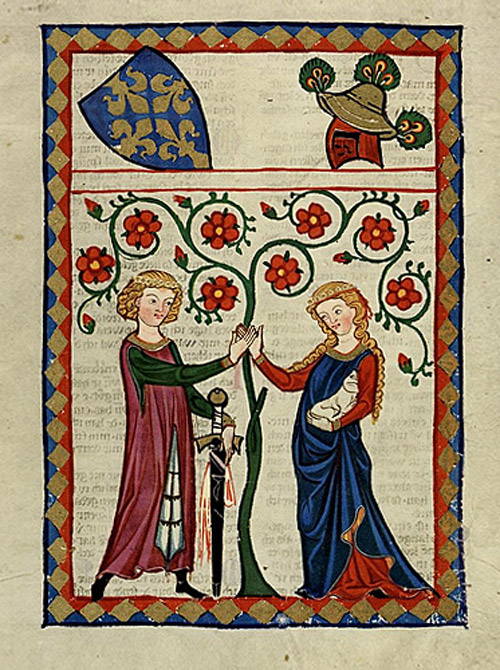

The Codex Manesse (f. 27v), a poem by Otto von Botenlauben.

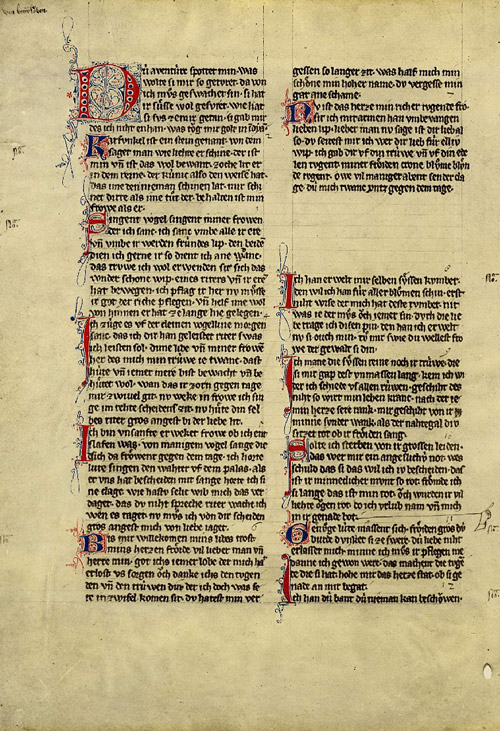

Poetry in the German language is preserved, in the first instance, in a small collection of songbooks (A, B, and C, the latter known as the Codex Manesse) and a few fragments associated with C. They are all from the end of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th centuries. The content is mainly love songs which are arranged by author, and without music. To these we must add D, E, H, and J, songbooks of mainly political and moral poems (Sangspruchdichtung), also arranged by author. The last of these manuscripts is of particular note because it is the only one from that period that includes the melodies. Then there is also a much larger group of lyric manuscripts from the 14th and 15th centuries, all of which feature poetry other than love songs (a, d, f, h, k, m, n, p, s, w, x, u, and v), and only four of which also include love songs (f, k, s, and x). Some of these songbooks (in particular the extensive k, with 940 songs) come from the master singer schools. In almost all the songs are arranged by author and very few include the melodies.

The Manesse Codex (f. 178r), a miniature of the poet Bernger von Horheim.

Two formal characteristics distinguish German troubadour song from its Romance-language counterpart. First, its asymmetrical metre, or heterometry. The scansion of the verse is based on the stressed syllables, which, together with the unstressed ones that follow them (and which can vary in number) form a sort of ‘musical’ or rhythmic beat. The metrical stress falls on the stressed syllables in nouns, verbs, and adjectives; so the metrical accent is inseparable from the linguistic one. For the same reason, therefore, it is more than likely that the metrical accent coincides with the notes that mark the melodic rhythm.

Secondly, German song is always isostrophic, in other words, each strophe follows the same rhyme pattern. To put it in troubadour terms, all the German compositions are in coblas unisonans. The greater variation in the order or number of strophes preserved in the songbooks that share this metrical uniformity seems to have been viewed as a positive element rather than a deficiency. Finally, it is worth mentioning that the political-didactic song (like the love song early on) is basically monostrophic (it has a single strophe). Generally, the (often numerous) strophes that make up each piece are written at different times and what unites them is only the most general subject matter.

Victor Millet Schröder (2017)

Bibliography

- Herchert, Gaby (2010): Einführung in den Minnesang, Darmstadt: WBG.

- Nagel, Bert (1971): Meistersang, Stuttgart: Metzler.

- Sayce, Olive (1982): The medieval German lyric 1150–1300. The development of its themes and forms in their European context, Oxford: Clarendon.

- Scholz, Manfred Günter (2016): Walther von der Vogelweide, Stuttgart: Metzler.

- Schweikle, Günther (1995): Minnesang, Stuttgart: Metzler.

- Tervooren, Helmut (2001): Sangspruchdichtung, Stuttgart: Metzler.

Some resources can be found at Mediaevum.de and at Literatura Alemana Medieval

A general electronic edition of German poetry is currently being prepared; see: Lyrik des deutschen Mittelalters